DUENDE

Gabe Montesanti

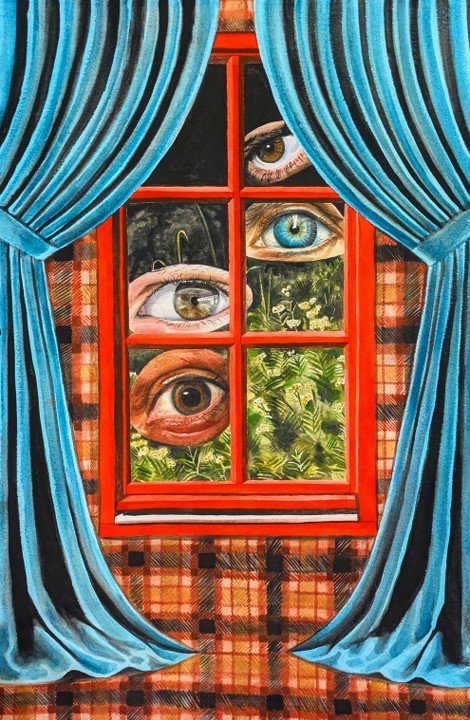

Chloe Hoffschneider, Somebody’s Watching, 2025. Watercolor, 15” x 22”

This is an excerpt from my book, Drag Thing: A Memoir of Mania and Mirrors, which is forthcoming from Arsenal Pulp Press in April 2026. The book chronicles my immersion in the drag scene in St. Louis, Missouri and the way in which my drag persona and my rapid-cycling mania gradually become indistinguishable from each other.

My friend Rocky once told me there are certain performances—certain moments in the drag community—that simply “do it” for her. She didn’t define “it,” but I understood. I feel it at almost every drag show whenever someone gets onstage and pulls out something that goes deeper than glamour, deeper than what some entertainers call “serving cunt.” One night, a trans drag creature with a toddler and unstable housing performs Wrabel’s “The Village,” a song dedicated to the trans community. I hold paint trays for them behind the stage curtain so that during a break in the lyrics, they can streak their face with the colors of the trans flag. I realize that I favor the songs about self-creation, performances in which the ragged, real, raw people in my spheres are taking off the mask, in a way, and reflecting the fucked-up things happening in the world.

Not all of the moments when I feel the mysterious phenomenon Rocky described involve performance. Once, before a drag show that welcomes newcomers, I met a man who looked to be in his early twenties sitting at the bar, drinking a ginger ale. He started opening up to me, like the swamp rose mallow I sometimes spot while driving by the Mississippi riverbank. I learned that he came to this show often and longed to get onstage, but certain things were holding him back besides his fear. “Ginger ale is about all I can afford,” he told me. We stared at the condensation on his glass until he told me he had a dress in the trunk of his car.

“Well shit, I have a new tube of lipstick you can have,” I said.

It was called Icon Era and had a non-budge matte finish. I told him he should try putting it on. When I checked his progress, the pigment was smeared all over his face and in his stubble. He grinned at me like a child.

“This shit is harder than it looks,” he said.

A few weeks later, I depart the house I share with my wife, Kelly, and drive across the Mississippi to learn some moves from an entertainer who is one of the best dancers I know. He meets me in his driveway and says he likes my old car. The sincerity of his sentiment makes me laugh. I don’t tell him that I’m lucky to be driving at all—that not long ago, I was too manic to get behind the wheel—but I do joke that I know how to pick ’em: my dad loves working on cars. I don’t know why I tell him this. Perhaps it’s because being in his presence has always made me feel comfortable, and I’ve been thinking about my dad a lot.

“Do you talk to your dad much?” he asks. I shake my head. “I get it,” he says. “I’m an African American trans boy with a pastor for a father.” We stand staring at my dirty car in silent reverie, and I feel “it.”

Thinking about Rocky’s statement about the undefinable quality of these moments, it strikes me that there exists an equivalent in writing and literature. The writer or artist must be willing to sit in the unknown and embrace the unanswerable questions. Federico García Lorca called it duende. In his essay “Theory and Play of the Duende,” he describes a dance contest in Jerez de la Frontera, where an eighty-year-old woman beat out beautiful and talented dancers who could easily have swept the grand prize. The old woman simply lifted her arms and stamped her foot. She possessed the undefinable ferocity of the duende. In the essay’s translation by A.S. Kline, the woman’s “moribund duende” swept the earth “with its wings made of rusty knives.”

When I was first learning about duende in the context of poetry, what struck me as crucial is that there are no answers in it. My teacher impressed upon us that duende is about being a mess, and often about being poor. It doesn’t require skill, just as it didn’t for the old woman in the dance competition. It often requires suffering. And that is what I witness in the performances and moments that stand out to me in drag. They are not the most technically advanced spectacles with the biggest stunts and the richest costumes. They are not always the numbers that would be most highly judged in competition, especially without knowing the entertainer’s background. But when performers explore the mystery—when I feel the duende—I briefly feel less alone.

***

It's truly no wonder that I’m so involved with drag; all the time I spend at queer bars, performing onstage, and in the attic constructing my next ensemble seem to be more effective than the mood stabilizers and anti-psychotics. My moods are shape-shifting. I feel both low and high simultaneously. Hopeless and ecstatic. Lethargic and wired. I have no discernible sleep schedule. I can pass out for fourteen hours or take only a quick nap instead of sleeping for a full night.

One week, I request to see my psychiatrist in person for a more thorough appointment since we typically meet online, and our meetings are as short as five minutes. When I arrive, the tech ushers me into a small room that contains only a desk with a computer and chair.

“She’s not coming in?” I ask, dumbstruck. “You want me to do a virtual appointment in this office?”

“Dr. Clancy works strictly from home,” he says, pulling the door shut after him.

I sit down, fuming, and tell Dr. Clancy onscreen that things are going fucking bad.

Sometimes it’s like the mania, even when it’s at a low simmer, seizes my ability to articulate. I’m in a perpetual rush. It feels impossible to explain to this doctor exactly how things are “bad.”

“What are you working on in therapy?” Dr. Clancy asks. Behind her, her two greyhounds are barking at something beyond the glass door.

I tell her about my last therapy session. Since I am suffering from a movement disorder called akathisia, a side effect of one of my medications, my therapist suggested we take off walking down a loud, industrial road. She was wearing cheetah-print heels. A light rain was falling. We trudged past a tire shop toward Party City as I yammered about how it felt living in a state of frequent mania episodes. No description seemed sufficient. I told her it was like being in a race car without pedals. Like being stung on the inside by a swarm of jellyfish.

“Well,” Dr. Clancy says, “sounds like you have a good therapist who will go to great lengths for you, and you’re making some progress. And you have such a healthy glow. I’m going to keep you on the current medication.”

I exit our video chat without saying goodbye and slam the door to the office as I leave. I know Dr. Clancy isn’t the right doctor for me, but I’m also aware that after I was diagnosed, it took six months on a waiting list to get to see her. I feel stuck in my situation, but a large part of me also feels relieved. I don’t challenge her because I’m afraid of a different doctor who would likely switch my protocol, leading to all new meds. With new meds comes new side effects. Often, they don’t help at all. It feels like I’m being scrambled on the inside, but I’m also prolific, inspired, superhuman. I think of the book I am reading by psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison, Touched with Fire, which links manic depression to creative genius throughout history. She poses the question, “Who would not want an illness that has among its symptoms elevated and expansive mood, inflated self-esteem, abundance of energy, less need for sleep, intensified sexuality, and—most germane to our argument here—sharpened and unusually creative thinking and increased productivity?”

I’m doing everything in my power to vanquish the mania. I’ve seen seven therapists and three psychiatrists. I’ve attended two group therapy scenarios and an outpatient clinic five days a week at a local Catholic hospital. I’ve tried dozens of medications, gained forty pounds, slept all the time, slept never. One drug requires eating 350 calories at bedtime, and one makes it so that I am never hungry. Still, I take my pills, practice mindfulness, attempt to meditate, and read multiple books about the disease by scholars and artists alike. But part of me knows, even if I don’t fully acknowledge it, that if I cling to the mania in even a small way, my feet will never have to find solid ground again.

***

One thing I tell no one—not my therapist and not Kelly—is that I often drive around the city to practice my lip-synchs. I seize the times when I’m allowed to drive, because if my mood is elevated, Kelly insists I hang up the keys. I prefer departing around golden hour, the time just before the sun sets. I drive east toward the Mississippi and roll down all the windows so the warm air hits my face. I turn up the music louder than is comfortable. I play the same song so many times that I have every syllable memorized: every quirk within the vocals, every drumbeat. Sometimes, I pull over and watch the original artist’s performance on YouTube to analyze their breathing, see what they do with their hands. Are their eyes shut? Is their stance wide? I’m not a trained singer. I have to learn performance strategies the way toddlers pick up language—the way I taught my dog Lady the word cow on the bumpy dirt roads back in Texas.

“You’re going to get carjacked, sitting on the side of the road in the city at night like that,” somebody tells me. But I don’t give a fuck. I feel impervious to danger. A few weeks ago, I blew out two tires flying over a speed bump in South City. Every time my therapist asks how my meditation practice is going, I think not of the app on my phone I am supposed to be using every morning, but of lip-synching to “I’m the Only One” by Melissa Etheridge hundreds of times in a row as I drive up and down River des Peres. Nothing makes me feel more present, more in my own body, than singing to other people’s voices. Call it meditation. Call it medication. Call it duende. It doesn’t matter to me.

Gabe Montesanti (she/they) is a queer writer and artist who resides in St. Louis, Missouri. She is the author of Brace for Impact: A Memoir (2022) and Drag Thing: A Memoir of Mania and Mirrors (2026). Gabe has been a roller derby player, a drag artist, and an educator. Preorder Drag Thing online at Left Bank Books or Arsenal Pulp Press, and find Gabe on Instagram @Gabemontesantiauthor.