Saltwater

Anne Pinkerton

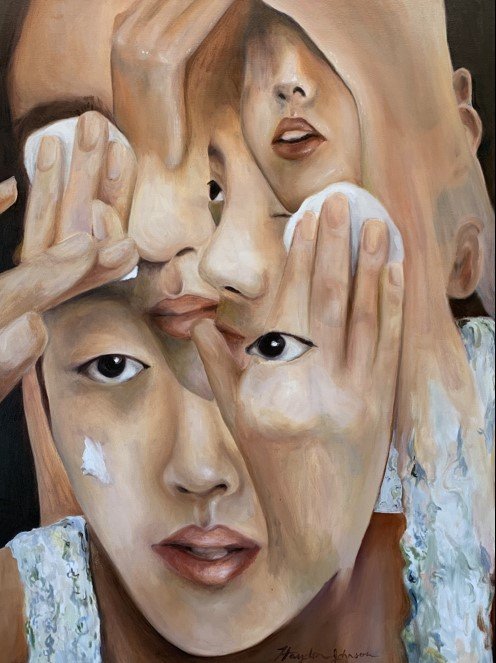

Hayden Johnson, The Ritual, 2023. Oil on canvas, 30’’ x 40’’

When we were married, and when he was in a generous mood, my husband used to say to me, “You’re pretty when you cry.”

I didn’t believe him, but I knew my tears usually made him feel bad, even when he hadn’t caused them. Sometimes, his statement made me feel my outpouring was accepted, even attractive; other times, he’d console me impatiently, as if my emotional display were inconvenient, a sense I’d had throughout my life in reaction to my crying. Even if the sideways compliment was a dumb attempt to get me to stop, it still seemed like a kindness when I was down.

That changed for sure when we split, washing a twenty-five-year relationship down the drain for good. On our last day, there was no kindness, and no prettiness either; once he was gone, I embodied the “ugly cry.” It suited the occasion, and there was no one around to bother. I let loose the pain of the loss through my whole face. Standing in the middle of our living room, relentless tears flooded my face, mucus clogged my nose, wild animal wails emanated from me, and my lungs heaved like I was an asthmatic on the verge of collapse. Crying like that makes me feel possessed.

I know how to cry.

I cry when I’m devasted by grief or elated by beauty. I cry when I’m furious and when I’m confused. I cry when I can’t have what I want; sometimes, I cry when I get it. I cry during really good commercials, movies, books, and songs. Especially the songs. If I’m already primed, I cry if I see a dead squirrel in the road. Sometimes, I laugh myself into a fit of tears. I’m very good at crying. I’m not so good at making myself stop. No one is. Even if they tell me I’m pretty.

***

In 2013, the photographer Rose-Lynn Fisher published a book of pictures called Topography of Tears. She described a weepy period she was experiencing when she became curious about what the product of crying might look like when magnified a zillion times. Fisher illustrated different kinds of tears—those generated under varying emotional circumstances—through photos of them, dried on slides, under a microscope. In that form, the tears were disembodied specimens, in different shades of textural grey. I first saw her images—a fascinating and complex new look—on social media, where they were shared widely.

A photo labeled “tears of grief” loosely resembles the layout of a spare suburban development as seen from a plane; “tears of change” shows crowded and dark granular formations; “onion tears” has a feathery, fern-like presentation; “laughing tears” looks like crackly ice with water bubbles underneath. “Tears of ending and beginning” evokes a vast terrain of permafrost.

I struggle to understand how beginnings and ends could have the same emotional provocation or final wet (or dry) presentation. The image made me remember the single-digit weather on the January day my marriage died. Surely, the crying that happens at beginnings—like when babies are born—looks warmer?

***

The idea that crying can be pretty feels like something Hollywood packaged and sold. A model-perfect actress with immaculate makeup and someone artfully dripping Visine onto her high cheeks while she gazes into the distance and softly weeps is not what I look like even without a cry becoming fully “ugly.” Hot red cheeks and eyes, an expression of agony, and mascara running down my cheeks—à la Alice Cooper—is more like it.

I suppose my ability to bring on tears in an instant could be beneficial as an actress. I would only have to summon the face of my beloved dead dog to embody a widow hearing that her husband has been lost at sea. I am often astonished at my talent for retraumatizing myself with memories of past losses that elicit sobs reminiscent of hearing the news the first time. And I feel like I’m the only one who can’t hold back tears, even when they aren’t helpful in any way—when instead, my emotional outpouring seems like a liability. But maybe it’s not just me.

***

In real life, crying is never cool. It’s humiliating at worst, humbling at least.

No one would argue that “crybaby” isn’t an insult, one often lobbed at me in childhood by other kids, and I don’t think they mocked me because they were jealous they couldn’t demonstrate their emotional range the way I could. No one wanted my sad all over them. I was a killjoy. So, they tried to make me feel weak and immature.

When I would get mired in a serious sob fest as a kid, my mom was intolerant. “Stop crying,” she’d demand. “You’re going to make yourself sick.” As an almost fifty-year-old, I still hear this line in my head when I’ve gone down the path of a serious wail and I can’t figure out how to pull myself back. It isn’t a nice internal mantra, and it doesn’t help. Also? I never got sick from crying.

***

Though Fisher’s photographs of tears under the microscope were numerous—and incredibly, even poetically, different from each other—there are technically only three kinds of tears. Basal tears are constant for the basic lubrication of your eye, and for keeping dust out. Not a true crying tear at all, just a daily, necessary drop of moisture for the workings of your eyeball.

Reflex tears are released when you’re chopping onions or get an eyelash stuck in your eye in order to wash out the offending element. Sometimes, reflex tears automatically produce antibodies because your body is smart and knows that foreign things that land in your eye may include bacteria. These first two kinds of tears are clearly physiologically functional and happen automatically.

The limbic system in the brain, which is associated with emotion, signals the lacrimal system of the eyes to produce the more complex emotional tears. Emotional tears, which scientists believe are unique to humans, were called “purposeless” by the clearly coldhearted Charles Darwin. Though I’ve often been embarrassed when I cried, I’ve also been comforted. Bawling can scare off some people, but others come to the rescue, wrap you in their arms.

***

In Susan Cain’s book Bittersweet she writes, “The word compassion literally means ‘to suffer together’. . . The sadness from which compassion springs is a pro-social emotion, an agent of connection and love. . . Sorrow and tears are one of the strongest bonding mechanisms we have.”

I flip the pages of her hardcover in bed one night. Cain writes that twenty-seven kinds of emotions have been identified by researchers. Why aren’t there as many types of tears? Or are there? Maybe it’s just that the differences are so far below the surface. And scientists require “purpose” in order for something to be validated.

***

In the car with my ex-husband on a drive to see a mutual friend, I played JD McPherson’s song, “Crying’s Just a Thing You Do.”

“See, someone finally wrote a song about me,” I said with a chuckle.

“It’s good you can cry so easily. It’s so hard for me,” he said, surprising me with the admission, though I knew it was true. I stopped trying to make a joke at my own expense. “It’s a good song,” he said.

I was surprised by that, too. Though we had played in bands together over the years and liked a lot of the same music, there were plenty of songs I loved that he disdained, and he liked to tell me how much he disdained them. The moment was oddly tender.

There are a lot of songs about crying, of course. Spotify keeps playing them as if Google is listening to me (of course the bots are listening). “Cry!” by Catherine Rose comes on, “CRY” by Julia Jacklin, “Cry” by the provocatively named Cigarettes After Sex. As if punctuation or caps changes their meaning. I envy a band named The Cry and feel a musical and relational kindship with their moody track “Alone” from an album called Beautiful Reasons. The lyrics are about being on a beach and a cliff acknowledging the deep sea, feeling adrift.

I know I’m not alone, but crying, fundamental though it is—and seemingly designed to forge bonds—is often enormously isolating. Then I discover whole playlists dedicated to the process, and feel a little better. Someone has curated a “Crying Mix,” another a “Sad Crying Mix”—oh, the hyperbole. The “Crying on the Dance Floor” playlist appeals, reminding me of Cain’s descriptions of how sad songs make her feel better.

As a teenager, I was typically angsty and had a hard time processing my feelings of insecurity, jealousy, first love. When I was upset, I’d lock myself in my room and listen to The Smiths and Joy Division just to help myself get at the feelings, crying myself dry in private.

***

Fun fact: women cry three to four times more than men, and more intensely. Unknown fact: why. Though I could guess. Even when we are witnessed inconveniently weeping, it is much more OK than seeing a man show his vulnerability through his eyes.

***

I used to be in a writing group with a woman named Heather Christle who, after releasing several other excellent titles, published a collection of poetry called The Crying Book. When I spotted it on the shelves of a local bookstore, instead of saying, “I know her!” or even buying it, I simply seethed with jealousy. I’m not proud. But it stings that she figured out how to own and use, even maximize on, the exact thing that haunted me most of my life.

***

Tears aren’t just comprised of water, or even just salt water. They also contain enzymes, lipids, metabolites, and electrolytes, like saliva does. And emotional tears include additional proteins. Researchers believe they may also excrete stress-inducing hormones, which, if true, proves they have a biological reason to exist, as well—a purpose!—and explains why some crying is so deeply relieving.

A single tear has three layers: an inner mucus layer, a watery middle layer, and an outer oily layer. The protein in emotional tears is what makes them the most dramatic, as they are the stickiest ones.

What I remember most from my first learnings about different tears is that the ones borne of true heartbreak, real suffering, and exquisite pain are physically thicker, making them roll down your cheeks more slowly, so that they are harder for another person to miss. I love this notion that our own bodies insist on slow motion at times like this, as if saying, “Look at me, look at me. I really need you to see my suffering right now and offer solace. Please hug me.”

***

The American Academy of Ophthalmology reports that we produce between fifteen and thirty gallons of tears over our lifetimes. That sounds like a lot, but also a little, to me. I feel like I cried an entire ocean’s worth over the loss of my big brother when he died. In his prime at forty-seven, he fell from a mountain he was hiking, and the suddenness shook me like nothing I’d ever experienced. That was an ugly cry times a hundred, a million, a countless amount. For months, I saturated pillows with my anguish, let my tears disperse in the water of the shower, bawled into the scruff of that old, now departed, dog.

***

Adults don’t cry from physical pain as much as children do. Though it’s harder for kids to explain what they’re going through when they get hurt, this strikes me as a kind of learned stoicism that makes me feel a little sorry for us grown-ups, with our evolved stiff upper lips. But without a parent around to show compassion for our owies, we clearly parent ourselves by stifling.

Not long after my divorce, I slipped on an angled set of wood stairs in my attic, falling several steps and landing with most of my weight very specifically on the second toe of my bare right foot. I knew instantly I’d done damage, and as the skin on the top of my foot quickly began to bloom purple and blue, I felt equal parts nauseated and scared. But as the sensation of serious pain overtook me, I mostly had an overwhelming need to cry. Maybe because I was alone with an injury for the first time in twenty-five years and I knew it would be a bitch to try to drive with a broken right foot, that heightened things. But cry I did—lots—and for a long time.

***

The last time I saw my grandmother was in a nursing facility she’d been moved into largely against her will. After living alone until she was ninety-three, a dangerous fall meant she succumbed at last. The transition took away much of her sparkly personality and a lot of her mental capacity. I wasn’t entirely sure she recognized me after not seeing her for a few months. But when I held her bony hand over the metal hospital bed railing during that last visit, she looked up at me with watery blue eyes and said, “I feel teary.”

Though sad, it made me feel extraordinarily connected, despite our previous ways of reaching each other—through hours-long talks while sipping from tall glasses of iced tea on the couch in the living room of the ranch house she’d inhabited most of her adult life. In the diminished setting of one less-than-homey room, I acknowledged what had been lost, but also the love that remained.

I squeezed her hand hard, and told her, “I feel teary too.”

***

A year after our divorce, I attended a concert by my ex-husband, who I am working on becoming friends with again. Walking up the street to the club, I realized I was unnecessarily rushing because, in the past, he likely would have needed me for something at a gig, and would have been anxious, which made me anxious. A sense of both relief and lack of purpose overcame me.

I settled into a seat next to a friend, ready for the first time to try to be a fan and not a partner. It started well enough. Then in the middle of his set, he dedicated a song to my deceased brother. He plucked the opening strains of “Ocean Rain” by Echo and the Bunnymen, and I was undone. We had listened to that song, full of love and despair, after a seemingly cosmic, very damaging hurricane delayed my brother’s funeral like a sign from above. It wasn’t an inside joke, but whatever an inside joke would be if it weren’t funny. A private understanding streaming from him to me, a covert message, a tribute only the two of us could understand. I shouldn’t have been shocked that he remembered the date of his performance was the anniversary of my brother’s death, but before he’d finished singing the first verse, I was completely unmoored.

I wonder what the tears I cried then would look like under a microscope? A lonely mountain range?

***

My favorite greeting cards for friends who are struggling were designed by Emily McDowell, who founded her whole company on “what to say when you don’t know what to say.” The “empathy cards” series, created after her experience with cancer, filled a gaping hole in the industry, acknowledging by its products that most cards are saccharine, avoidant, or downright stupid. She made the first greeting card that read plainly, “There is no good card for this.”

Her “crying card” has been sent to several of my most important people. It acknowledges a humorous alternative to Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief:

crying in public

crying in the car

crying alone while watching TV

crying at work

crying when you’re a little drunk

This card makes me feel seen unlike any other.

***

Work is the most terrifying place for my superpower to turn on me. In moments of stress or anger, I also tend to well with tears. Professional settings are, by definition, set up to discourage the demonstration of personal feelings like that.

In a private meeting with my boss, during which she gave me feedback about being more effective in meetings with others, she cautioned me to pause when my frustration builds, to talk less, to wait to respond. And she acknowledged that “it sucks.”

I felt my heat rise in my face as I knew the unwanted waterworks were coming. She simply gave me a tissue and said, “I know. I cried when a coach told me the same thing.” Her vulnerable confession strengthened our relationship, just like tears do.

***

In a 2016 article in Time magazine, Ad Vingerhoets, “the world’s foremost expert on crying,” admits that there is still much unknown about this utterly common—nearly universal—human experience. Yet, he declares, ‘“Tears are of extreme relevance for human nature. We cry because we need other people.”

“So, Darwin,” he says with a laugh, “was totally wrong.”’

***

It’s been a year since my ex and I had to put down that dear old dog. Though we’d been apart many months by then, we made the decision together, spent the last day with her together, and did that hardest thing together.

Today, I see him when I drop the dogs at his place—one we had back then, plus the new addition, another sassy girl. We’ve easily negotiated shared pet custody, satisfying for all. But we both remember what day it is. We pull out our phones and scroll through old photos and videos, remembering the pup we wish was here. And we cry, together.

I no longer worry whether or not I look pretty.

Anne Pinkerton is the author of the memoir Were You Close?: A Sister's Quest to Know the Brother She Lost. Her essays and poems have appeared in Hippocampus Magazine, Ars Medica, River Teeth's “Beautiful Things,” The Keepthings, and The Sunlight Press, among other publications.