al sharpton.

Mars Robinson

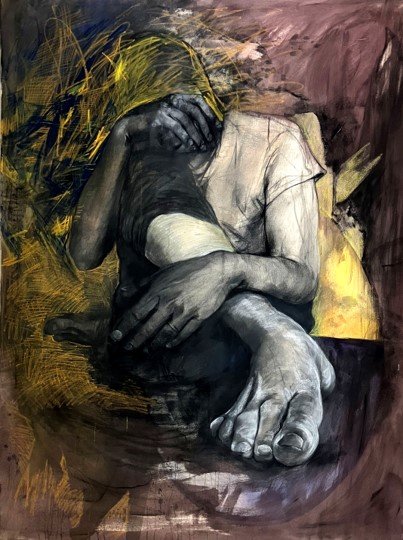

Toni Parker, A Mother at Rest, 2025. Charcoal, chalk, and water-soluble crayon on raw canvas, 6’ x 4’

When Timothy Thomas Jr. died, Al Sharpton was fat and I was around ten. The civil rights leader flew in after the funeral and laid roses at the fence where the boy was left crumpled, Black, young, and murdered. The news called him a man. I had not yet come to understand why. I pointed my feet in the bathtub and listened to my parents. My father’s suit hung from his bedroom door. There would be a funeral. He would be there. My father, not Al Sharpton. I wasn’t concerned with Al Sharpton.

Ask your parents how long the Cincinnati riots lasted. Ask them how long the windows broke. Ask them how many buildings caught on fire. Ask them how much blood spilled on the streets and down the gutters and past the sewer rats. Ask them how many Black tears they watched fall. Ask them how many teeth were chipped. Ask them how many jobs were lost. Ask them how much was stolen. Ask them how much soap washed how much skin—bruised skin, torn skin, cut skin. Ask them if they really have any idea. Ask them how they would know.

I remember getting my hair wet, and lord knows it is not supposed to be wet. I could feel the tension. The police will start something. You know they’ll start something. I don’t remember who said it, my mother or my father, but the words snaked into the bathroom and grew until I couldn’t breathe. I put my head underwater so I wouldn’t drown.

Ask your parents the name that taught them life wasn’t fair. Ask them if it was Emmet Till. Ask them if it was George Stinney Jr. Ask them if it was Addie Mae, Cynthia, Carole with the ‘e’, and Carol without the ‘e’. Ask them if it was Rodney King. Ask them if it was Roger Owensby Jr. Ask them if it was Sean Bell. Ask them if it was Trayvon Martin. Ask them if it was Eric Garner. Ask them if it was Tamir Rice. Ask them if it was Samuel DuBose. Ask them if it was Sandra Bland or Breonna Taylor or Ahmaud Arbery. Ask them if they were late or early to realize. Ask them if Al Sharpton was in the pictures, if he was skinny or fat.

Timothy Thomas Jr. taught me life was unfair when I was almost ten, when the news called us nigger by printing the word thug. When the streets downtown smelled of piss and sweat and rotted food, rotted wood. Why couldn’t we run? Why wouldn’t we run in streets like that?

Back when Al Sharpton was fat, my dad put on a tie and headed out the door. He went alone. Because every protest was a part of the riots. Because every line of linked arms was just as dangerous as the line of assault rifles across the street. The funeral was as lovely as funerals are for nineteen-year-old boys. From what I’ve heard. From what I’ve read. When I was nine, nineteen sounded so grown. Nineteen. My father was forty-one. It must have sounded very young to him. Nineteen.

After the funeral, they shot the crowd with bean bags, by the way. But my father came home safe. They preferred to hit women and children. I used to think that it mattered if the violence reached the children. I guess it would matter, if they didn’t treat our children like adults.

Ask your parents who ‘they’ are. Ask them if ‘they’ are slave breeders, hopping up and down inside of a raped woman to make some more livestock. Ask them if ‘they’ are slave catchers, cops before the badges. Ask if ‘they’ are cops, slave catchers after the badges. Ask if ‘they’ are bystanders, who feel the tension and change the subject. Ask if ‘they’ are turncoats. Ask if ‘they’ are media pundits. Ask if ‘they’ are politicians. Ask if ‘they’ are freedom fighters. Ask if ‘they’ are congress killers running up stone stairs.

Al Sharpton was starting to lose weight when Stephen Roach pulled my mother over. Years after the cop shot and killed a nineteen-year-old boy in an alley. I’ve never known I was looking a murderer in the eye, but it must have been a novel experience for her. I wonder if she tried not to think about it. I wonder if her breath caught when she recognized the face. I wonder if she didn’t know until she read the name on the ticket. I wonder if she took me to court with her to burn the image of a murderer in my mind. I should ask her.

But then again, Al Sharpton was skinny when Michael Brown died. He wasn’t fat anymore at Daunte Wright’s funeral. He was svelte at George Floyd’s. I wonder if Al Sharpton lost all that weight running from funeral to funeral.

I was twenty-three when I started applying Black lives to the question: If a Black person is murdered and there’s no camera around to catch it, is it a justified killing? A tree makes a sound when it falls and we do too. Our bodies thud, crack, squelch. Our mouths bubble, sputter, and gulp.

Ask your parents if they’ve thought about the cleansing process. Ask how to get blood out of vehicle upholstery. Ask how to pressure wash remains off cement. Ask them how to get stains out of t-shirts, and jerseys, and Nike shoes, and bookbags.

Al Sharpton looked old as fuck by the time Philando Castile’s daughter tried to console Diamond Reynolds, who was inconsolable. The lines around his mouth grooved in so deep, like they were carved into wood. From all that talking. From all that dying. From all that profit. And all those unpaid taxes. Maybe he smells the tears, like a hungry bloodhound, and that’s how he gets to the service in time. He wasn’t at Timothy Thomas Jr.’s funeral, though. He wasn’t hungry then. He was fat.

When my dad came home after the funeral, I stopped drowning in air. I remember that his knuckles looked so big to me then. When he beat on a drum, when he played a piano, when he danced to a song. I remember repeating his talking points about the police, about us Blacks, about slavery, and punctuating them with a Herbie Hancock reference, or a Count Basie reference, or a Billie Holiday reference. To impress people like him then. People I am like now.

Ask your parents about strange fruit. Ask if they know how it tastes.

I was ten, looking forward to the day that I didn’t worry if my father would make it home. Al Sharpton was fat then.

He’s not now, but I still worry.

Mars Robinson (she/her) is a fat, Black, cis poet and speculative fiction writer, as well as a graduate of DePaul University's Creative Writing and Publishing program (MFA) and University of Cincinnati's Creative Writing and Rhetoric & Professional Writing programs (BA). Above all, she is her mother's daughter. Reach Mars on Instagram @marsnoblerobinson.